HSB Living Lab

Future inhabitants under the microscopeIn this unique living laboratory students and researchers live side by side, as we research their living habits, as well as the materials and technology of crucial importance for how we will build the future. Based on the facts we obtain, we are formulating the change we see as necessary to provide better conditions for future generations.

In the autumn of 2013 we made the decision, as the first external partner, to join the project HSB Living Lab. This decision resulted in phase one, which meant that we contributed to a brick-and-mortar location along with our other partners, HSB, Chalmers and Johanneberg Science Park. Today, we are twelve partners. HSB Living Lab is a unique research project in which new technological, social and architectural innovations will be tested in real life. For ten years, the house will serve as a living laboratory and home to about 40 students and researchers.

It is an arena for developing new ways to build and shape the future of housing, as well as a platform for work between collaboration partners. It will feature a residential section with student housing and an exhibition area, including offices, meeting rooms and showrooms for research. The project is one of a kind, as it is the first house where people will live while the research goes on.

“Where yesterday’s architects might consider themselves to be finished, we are now continuing to develop our work in the building and its programming.”

– Peter Elfstrand

Our role as architects

We of course designed the building, but it is much more than just a physical shelter. We designed the conditions for a changing research platform, adaptable from both a financial and functional standpoint, based on the scientific work to be conducted in the building. The structure is based on modules, which are part of the research and which will be evaluated for future housing solutions and assessed as, for example, infill projects on a street or as solitary structures in an open area. Parts of these units could also be placed on a roof to create a three-dimensional property.

“Where yesterday’s architects might consider themselves to be finished, we are now continuing to develop our work in the building and its programming. It is a special and exciting situation for us to be working on a project where the goal is not a finished structure, but rather a constantly updated, changing process,” sais project architect Peter Elfstrand.

Why are things the way they are today? How did they get this way? Is there anything we can change, and if so, how? Do things correspond with what we see as the needs of our times?

As architects, we have a great deal of responsibility towards social-centric building and thinking in a broader perspective with a long-term view. What we plan and build today must be adapted for the future, with the largest foundation in reality. But what can we really know about the future? Nothing, many would argue, but our commitment to the HSB Living Lab is a unique opportunity for us to participate in the dialogue on research and housing, both in the present and in the future. Along the way, we have the opportunity to ask questions such as: Why are things the way they are today? How did they get this way? Is there anything we can change, and if so, how? Do things correspond with what we see as the needs of our times?

What (and what not) to do

It is easy to get caught up in what not to do, and hindsight is of course 20-20. For example, many of us agree that it is not a good idea to build homes based on laws and rules derived from the 1940s and 1950s – something the trade still does today.

This hardly results in buildings for the future that are tailor-made for generations with very different needs and outlooks on life than their parents had. Research similar to what we are entering into with HSB Living Lab has been done before. References include kitchen studies in the People’s Home (Folkhemmet) in the Swedish 1930s and the Case Study Houses that were built in the United States in the post-War period as an experiment to remedy the then acute housing shortage. Many experiments like these can be written off as a flop today, as they were not at all on the mark about what people wanted. So what is there to suggest that this living lab will achieve success?

“We are twelve equally involved and very committed partners; the central focus here is cooperation between academia and industry. Now we have reached a level where we are starting to work together in earnest. The results are hotly anticipated, but the most important thing is perhaps to always focus on people,” says Peter Elfstrand.

We see it as a blank canvas, something that can stand to be rearranged.

People in focus

The house is of course a technical stronghold, including hundreds of sensors that monitor and analyse the residents’ lifestyle and habits. How often and when the window and the refrigerator open is measured, for example, to determine when it makes sense to start cooling. Electricity and water are two major areas that will be analysed, but of course, no one wants the residents to feel “monitored”. For this reason, all of the data is coded. The residents should view the building first and foremost as a home, while all partners should have the opportunity to ‘dress the house’ with their specific knowledge and research. The basis for this is democratic design.

A democratic design

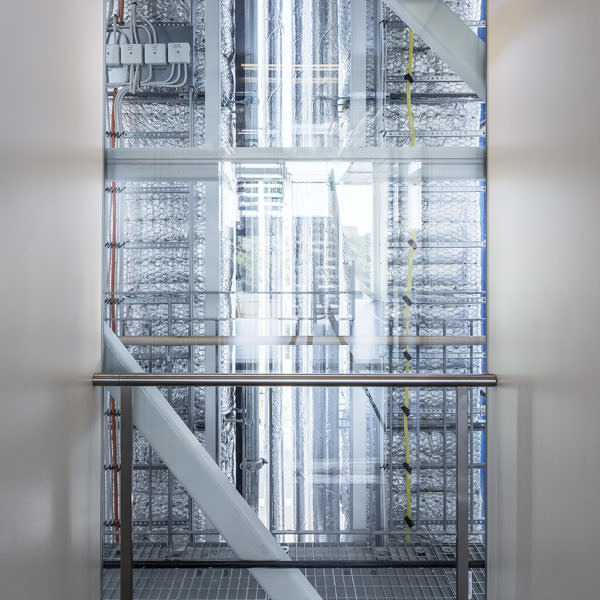

Some criticisms and questions have been posed regarding the aesthetics of the building. No, it does not look like something out of a sci-fi movie, and there are good reasons for this. The goal was never to create an iconic building that takes the focus off the content, but rather a platform that can be changed and thus be living and inclusive. Our role as the architects of this project is not to point to answers or solutions in advance, but to create conditions for them to grow forth. We see it as a blank canvas, something that can stand to be rearranged. This results in a generic design with standard dimensions to the greatest possible extent, including interchangeable panels and systems. The building’s aesthetics are consistent with these basic dimensions.

Photo: Felix Gerlach

Photo: Felix Gerlach Photo: Felix Gerlach

Photo: Felix Gerlach Photo: Felix Gerlach

Photo: Felix Gerlach Photo: Felix Gerlach

Photo: Felix Gerlach

“In this project, we have not been able to take anything for granted. We’ve thrown everything up in the air and tested the boundaries between private, common and public. We have held focus groups with everything from behavioural scientists to sailboat manufacturers with expertise in galleys. Not taking anything for granted has been a great challenge, but it is also the driving force,” says Peter Elfstrand.

A major challenge

Being completely self-sustaining as an architect in a project, asking questions, pushing them forward and making sure they are investigated and answered – these things are challenging and go against our traditions in some ways. At the same time, we see it as a strength for us to have the opportunity to be this experimental and conceptual. We expect to learn a lot through the projects we carry out in the house, and probably from the mistakes we make too. One of our studies, called the Next Generation Kitchen, has already resulted in a product that students from Rice University in Texas are testing in the prototype phase in the house. It is called BioBlend and it is a waste grinder that creates finely ground compost within a closed system. We are also researching future storage in the house and solar panels on the façade. A lot can happen in ten years, but perhaps what we will learn the most from are the social aspects of how we will, and will want to live in the future. In effect, our participation in the project means that we have clients at arm’s length with which to conduct dialogues.

The greatest advantage for us as architects is perhaps that based on the facts we obtain, we can be involved in formulating the change we are seeing, to create a better environment for future generations. When it comes to building the future of sustainable cities and houses, the architect has an important and decisive role. We are inspecting, analysing and challenging this role now to become even better at what we do.

The team behind this project

- Peter Elfstrand Architect

- Cecilia Holmström Architect SAR/MSA, Strategic Advisor, Housing

- Linnea Henriksson

- Beryl Malmborg Structural Engineer

- Lars Persson Structural Engineer

- Peter Sallmén Architect

- Lina Rengstedt Architect

Contact

Contributing areas of expertise

Sustainability

Sustainable development is about meeting basic needs in the present without compromising our possibilities of continuing to do so in the future. Environmental, social and economic sustainability is our Alpha and Omega – a key strand of the Tengbom DNA on which there is no compromise.

Read more about Sustainability

Residential

We design houses where people can live and lead a good life. We are committed to creating lasting values and environments that make a difference and contribute to high architectural quality that enrich the city. The ambition ranges from new construction to refurbishments and conversions, and beyond.

Read more about Residential